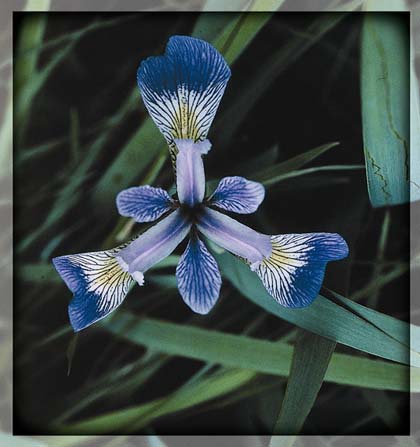

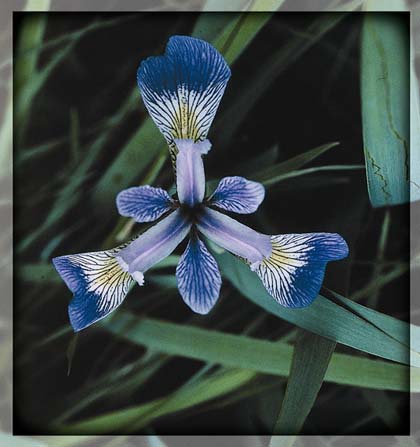

Blue flag, one of our more majestic and unusual midspring wildflowers, is a member of the regal Iris family that has impressed both naturalists and gardeners through the ages. Yet the plant received only a mediocre review from none other than Henry David Thoreau. “How completely all character is expressed by flowers,” the essayist wrote. “This is a little too showy and gaudy, like some women’s bonnets.”

Without doubt, the blue flag is showy, but that’s part of its means of survival. At a time of year when many blossoms vie for the attention of nectar-hunting pollinators, its big, showy blossoms are able to flag down many passing bees. The flowers offer plenty of room to land and ample veining to act as a guide to the sweets inside.

Blue flag’s blossom has evolved to move pollen very efficiently from flower to flower. Bees can’t help rubbing against the pollen-bearing anther, located overhead and positioned so that the grains can’t fall onto the stigma, self-fertilize, and lead to poor-quality seeds. The sticky stigma is situated such that the visiting bee will deposit pollen from other flowers.

A-turn-of-the-century plant naturalist, appropriately named Clarence M. Weed, found that irises like the blue flag are particularly susceptible to thievery. While the flowers are adapted to large bumblebees, many flies, skipper butterflies, moths, and other insects are also attracted to them and usually don’t transfer pollen. Nevertheless, the iris has plenty of nectar to go around, and it’s perhaps no accident that the blue flag is a denizen of wet places—swamps and moist fields—making production of large amounts of nectar easy.

The leaves, too, are specially designed. Grasslike and vertical, they allow the sunlight to penetrate through the mass of vegetation in a tightly packed colony of plants. What’s more, unlike broad-leafed plants, the iris can assimilate light on both sides of its leaf, not just the upper surface.

Larger blue flag (Iris versicolor) is one of the most visible and most representative of the wild irises east of the Mississippi. Although not rare today, the species was more plentiful in the days when there were more pastures and swamps, so many of which have been drained, filled, or bulldozed for fields and, more recently, subdivisions and shopping centers. Their blooming season in the Northeast runs from late May through June. When they’ve been left undisturbed, these irises often form impressive colonies, which may be in shaded swamps or open meadows, but almost always where their roots can remain moist most of the year.

Wild irises are not overly common and the flowers shouldn’t be picked, no matter how tempting. Although blue flags are perennials and spread from their rhizomes, they also depend on their seeds for propagation. Besides, said Mabel Osgood Wright, “this iris must surely be seen in its home to be known in anything but outline. If many flowers of wood and field lose quality away from their surroundings, the herbaceous flowers of moist lands and waterways do so in far greater degree.” Even the critical Thoreau admitted, “It belongs to the meadow and ornaments it much.”

Regal History

The iris has had a lofty and regal history. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote of the flower:

Born in the purple, born to joy and pleasance

Thou dost not toil nor spin

But makest glad and radiant with thy presence

The meadow and the lin.

The name comes from the Greek goddess Iris, who was a messenger between humans and the gods atop Mount Olympus. Wherever she went, a rainbow followed her. Whenever the ancient Greeks saw a rainbow in the sky, it was a sign that Iris was delivering a message to someone. Thus, iris came to mean “rainbow” and, used as the generic name of these plants, reflects the variety of colors sported by many species. One of the goddess Iris’s duties was to guide the souls of dead women to the afterworld, and so Greeks often planted the flowers next to graves.

The ancients consider the iris a symbol of power and majesty. Egyptian kings used the design of the blossom on their scepters and placed it on the brow of the Sphinx, believing its three major petals to be symbols of faith, wisdom, and valor. Modern use of the iris as a royal symbol may trace back to Clovis, a sixth-century king of the Franks. According to one legend, a large force of Goths trapped his army, with his back up against the Rhine River near Cologne. As he searched for a way to escape, Clovis noticed in the distance a large colony of golden irises extending far out into the river. He realized this was a sign that the water was shallow enough there for his troops to cross. In another version of the tale, Clovis was able to sneak across the river and attack the rear guard of the Goths by finding flags growing in a shallow area. Yet another legend involving Clovis is more colorful, if not believable. The king was having a hard time at war, constantly losing battles. One day an angel appeared to a holy man, explaining that Clovis needed to get rid of his coat of arms—three black toads—and replace it with three irises. The angel gave the man a shield with the irises on a bright blue background. The holy man brought the shield to Clovis’s wife, Queen Clotilde, who gave it to the king. Clovis got rid of the toads, used the new symbol, and began to win battles. Whatever the reason, angelic or riparian, Clovis adopted the iris as his family’s badge.

Perhaps knowing this tradition, King Louis VII of France selected the iris as his house emblem when he was a young Crusader. It thus became the fleur-de-lis, fleur-de-lys, or fleur-de-luce, all corruptions of fleur-de-Louis, “flower of Louis.” (Another theory has it that the fleur-de-lis is a lily—lis, the French word for “lily”; and in The Winter’s Tale, Shakespeare spoke of “lilies of all kinds, the fleur-de-luce being one.”) Our blue flag, a different species from the white iris of Louis, is sometimes called the American fleur-de-lis. Some authorities claim the flowers are commonly called flags because Louis, Clovis, and some other rulers in Europe frequently employed the design on flags and banners. A simpler and more probable explanation, however, is that iris leaves look like reeds, the Middle English word for which was flagge.

Less regal are some of the other folk names for our own Iris versicolor: poison flag, liver lily, snake lily, dragon flower, and dagger flower. Some of these refer to the shape of the blossom (dragon) or the leaf (dagger); the Old English word for the plant was segg, which was a small sword. Others reflect the plant’s long history as a medicinal herb.

Iris versicolor has probably been used in medicine more extensively than any other member of its clan. American Indians dug the roots from wild plants and even cultivated colonies near ponds. They used the root to treat stomach problems and dropsy, and as an emetic, a laxative, and a poultice. Members of some western tribes carried the root of another species to prevent snakebites.

“It is excellent in removing humor from the system, much more so than the outrageous mercury and much more safe,” said the Ladies’ Indispensable Assistant in 1852. This advice did not suggest that a clown would turn dour from consuming it; this “humor” was a bodily fluid, and the writer presumably meant a “bad humor” that would cause sickness.

The “rhizome,” or creeping rootstock, contains a powerful, acrid resin so strong that many modern authorities warn against its internal use. This may be why the plant is also called poison flag. Some herbalists in the past, however, considered the plant valuable in treating chronic vomiting, heartburn, liver and gall bladder ailments, sinus problems, colic, gastritis, enteritis, syphilis, scrofula, skin diseases, and even migraines. Drugs called Iridin or Irisin, used as diuretics, were once produced from the plant, which was long listed in the U.S. Pharmacopoeia, a catalogue of accepted drugs. Modern research indicates the root may have the ability to increase the rate at which fat is converted into waste, and an iris has been used in India as a treatment for obesity.

Mixed with water, blue flag flowers can produce a blue dye that acts like litmus paper, turning red when exposed to an acid, or back to blue if the substance is alkaline.

Various species, particularly European ones, are known as orris root—orris being a corruption of the word iris. After drying a few months, their roots gain a sweet scent, not unlike that of violets. Ground into powder, these roots were once made into little pomander balls that were carried by the wealthy as a perfume. This same powder was also carried by witches who, it was said, induced abortions with it.

In the 19th century, growing Iris florentina was a major industry in parts of Italy, particularly the Chianti region of Tuscany, which shipped the dried rootstock to Florentine perfumeries. Florence, whose city seal bears the likeness of an iris, is still a center of interest in the plants and hosts the International Iris Trials, a competition for growers. Iris roots are still used as fragrances in fancy soaps, cosmetics, and liquid perfumes.

The French, who enjoy all sorts of drinks made from plants, once used roasted iris seeds as a coffee. The leaves have been used to make a green dye, and the root to make black dye and ink.

Throughout North America at least 47 species of iris exist, some of them garden escapes native to other continents. One botanist claimed that just in the southeastern United States, nearly 100 different species can be found, many of them in southern Florida. However, current taxonomical researchers have reclassified about 65 previously defined species into one, the Dixie iris (I. hexagona). Worldwide, more than 150 species grow in the north temperate zone, much to the pleasure of gardeners specializing in this handsome genus.

I. versicolor, also called the harlequin blue flag, ranges wild from the East Coast to Wisconsin and from Canada south to Virginia. It is also found in Idaho. Of several beautiful western species, the most widespread is the western blue flag (I. missouriensis), found from British Columbia to southern California and eastward to the Mississippi. American Indians used fibers from the outer edges of the leaves to make surprisingly strong rope, string, and netting, as well as fabric for bags. Weaving the fibers into rope was a tedious task. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Plant Data Center reports that it took an Indian nearly six weeks to make 12 feet of iris rope.

Almost all irises are showy and colorful. Some are actually shocking to encounter in a verdant wooded wetland. Blue, purple, lilac, orange, white, and yellow kinds are known in North America. The yellow iris (I. pseudacorus), an introduced species from Europe now found as an escape in most states and provinces, was used in ancient herbal medicines.

Irises are in turn members of the Iris family (Iridaceae), which consists of more than 90 genera and 1,800 species worldwide, most of them growing in Africa. The Iris family includes the modest little blue-eyed grasses of our spring fields, and the springtime favorites of gardeners, the crocuses. Many irises bear a resemblance to many orchids, and so it’s not surprising that the Iris family is classified as fairly closely related to the Orchid family (Orchidaceae).

This is a chapter from The Secrets of Wildflowers.

Text and photo Copyright 2003 Jack Sanders. All rights reserved.